|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

Let

us now return to our division between descending and ascending energies,

which are to be found in constant movement on the intermediary plane, the

earth, between heaven and the underground world. It is those energies that

unite and bind these polarities, and their characteristics are incarnate

in the numina, the stars, and vegetation, in the perpetual cosmic battle.

The deities are these energies or attributes of the indissoluble unity,

of the unknown and invisible god dwelling in the remotest heights of heaven,

perpetually inventing himself, in all immobility, and manifesting himself

through descending emanations. Having circulated among all things, and

shaped them, these emanations rise once more to him, in the alternating

and cyclical rhythm of the universal energy expressing themselves on three

levels: heaven, earth, and the subterranean world. It is the gods, then,

who are the intermediaries par excellence of the cosmic plan, and their

ongoing interaction bears the names of everything created.

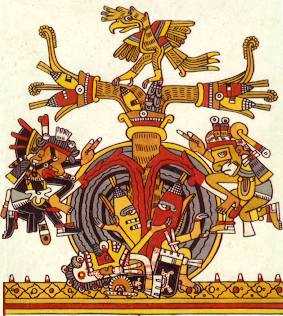

The Mesoamerican Quetzalcoatl, and the Incan Viracocha (together with many other, analogous, Precolumbian deities, such as the Mayan Gukumatz-Kukulkan and the Colombian Bochica), clearly illustrate this interrelationship of the rising and falling that occurs in the very body of the deity. Indeed, these gods incarnate-as men. They die, rise, and ascend once more to their dwelling place. In the particular case of Quetzalcoatl, his very name ("Plumed Serpent") symbolizes the conjunction of opposites, the union of the creeping with the flying, the energies represented by earth and air, which are opposed to, and do battle with, each other, in the fashion of, and in correspondence with, the other elements of the cosmos: water and fire.1 In fact, the descending-and-ascending energy incarnated and synthesized by Quetzalcoatl unfolds on the level of earth, where it manifests itself in two pairs of symmetrical opposites, as we have said above. Quetzalcoatl is a symbol of the bipolar, above-and-below, axial energy, which, upon finding a suitable medium, expresses itself, generating the horizontal plane. Where this plane is concerned, the falling-and-rising axial energy is central: in dividing into two pairs of contraries, to which the descending-ascending opposition is transferred in a cruciform figure, it abides at the fifth point-at the immutable intersection. After all, it is its force that has created the figure, just as it is to this axis that it always returns, having constantly to ensure its equilibrium by way of the interplay of the tensions of its own structure-that is, the tensions of all that it is.

At this stage, having once more set forth the role of the axis, and of the number five and its attribution to Quetzalcoatl, let us now turn our attention to the other four points of the horizontal plane-that is, the falling-and-rising energy projected into the cosmos and extended into all things: into the four corners of the world, into the four colors, into the four seasons of time, and especially, in this case, into the four apparent states or elements in which "matter" is manifested. "Matter" is such in virtue of the cruciform interaction of these elements, and their movement in the form of an alternating round in which (in space and time), in precise fashion, they succeed one another, with one of them always predominating over the others. This predominance can be clearly appreciated in the division of the cycle into five great eras corresponding to these elements, a division proper to the ancient American civilizations.2 Returning to Quetzalcoatl, let us point out that there are a number of versions of the story of this mythical personage, which likewise correspond to the verticality of his functions as a god, that is, as emissary of the divine energies. All of these versions, however, converge in this schema of the descending-and-ascending, with certain particular or secondary characteristics which it is interesting to observe. Quetzalcoatl is god of fire, and in this sense his sacrifice repeats that of Nanahuatzin, the creator (a repulsive god covered with sores) in Teotihuacan, also identified with Huehueteotl. He is a child of the pair who have emanated from Ometeotl-Ometecutli and Omecihuatl-and, as such, a descending god. He is also god of the air, and, accordingly, divine breath and messenger. As deity of the wind, he is at the "beginning of water," at the "heart of water," since he clears the path for the rains, which he regularly proclaimed at the close of the dry season, emissary that he is of the regeneration of nature. In the same sense, as herald of the morning, he leads the sun in its course, and proclaims the new day, acting as bond between the darkness of night and the morning light. This dual role is likewise to be remarked in his function as god of twins, and especially in the bond he maintains with his own twin, Xolotl-Venus as morning star and evening star-who represents the dark, moist, subterranean part of the dual reality of which Quetzalcoatl signifies the luminous portion. In Teotihuacan, and in other Mesoamerican manifestations, this deity is associated with Tlaloc and therefore with rain and waters-also with the moon-; and for that reason with fecundation, generation, and vegetation. This links him with the deities of earth and nature, as well. He joins in himself the four elements that are complemented in him, and as descending-and-ascending deity he constantly recycles the universe.3 He is the divine potency in action, the word and breath of that being, now old, called the world. This intermediary role has always been attributed to Quetzalcoatl-and hence his close connection with the sun-since he is the builder of the world, the demiurge, just as he is the column supporting the cosmos, as well as the creator of man from the bones of the deceased, which are irrigated with the blood of his dismemberment, as with other gods of various traditions. He is also the maintainer, and as such the "discoverer," of maize, that nutriment of man. He is educator, psychopompos: he has bestowed science, and he dispenses knowledge of the cosmogonic and theurgic mysteries. He is likewise savior and deliverer, inasmuch as the revelation and incarnation of this being promotes in us initiation into the True Man, the Archetypal Man par excellence, the model, symbol, and example to be followed ritually by the sages, warriors, artists, and farmers who have shaped the community of the Precolumbian peoples. Quetzalcoatl is in the beginning (as creator), in the middle (as sustainer), and in the end (as hope of return, or the opportunity to be received by present man in his interiority), since, traditionally, and unanimously, his messianic return is expected on the native continent. As symbol of the planet Venus, Quetzalcoatl traverses the underground world, and emerges resplendent from the murky trials to which he is subjected.4 Quetzalcoatl Topiltzin, King of Tula, the god's historical image, does the same thing, and repeats a truly underground (or inframundane) journey, that includes intoxication and incest-as symbols of what is outside or beyond the law-before his culmination as bright star of the dawn. This central deity of the American peoples-who know him under different names-gathers the divine activity within himself, and therefore is the most celebrated image of the potentiality of the sacred. The deities symbolized by the sun and the moon also have one ascending aspect or movement, and another descending. The sun executes the former from midnight to noon, and the second from noon to midnight, passing through sunrise and sunset-that is, in four steps, which it duplicates, yearly, from the winter solstice to the summer solstice and then vice versa, passing through the equinoxes. The moon realizes its rising (or waxing) period from new moon to full moon, and its falling (or waning) period from the latter to the former. It likewise performs them in four stages, which are the seven-day weeks of a twenty-eight-day month. The year, meanwhile, consists of thirteen moons, for a total of fifty-two weeks of seven days (7 x 52 = 364). But not only must we consider this movement of rising/falling energies in each star in particular: it must also be taken into account that, in the sun/moon binomial, the sun is regarded as ascending (active) and the moon as descending (passive), which, generally speaking, the Precolumbian traditions have consequently transformed into husband and wife, or brother and sister, or heaven and earth. And as heaven is father and earth is mother, these same values are transferred to the firmament, to be represented by the sun and the moon as intermediary deities. At the same time, the sun is identified with fire and

the moon with water, air being associated with the solar expansion, and

earth with its receipt of the moon and its subsequent fecundation. Likewise,

we observe that the descending deities must be celestial (otherwise they

could not descend), and inversely, the ascending deities must be linked

with earth. By way of immediate conclusion, the moon-and in some cases

the sun, as well, especially the noonday sun-is ascending insofar as it

is regarded in its relationship with the earth, growth, and vegetation,

and descending in its relationship with the sky, basically in virtue of

its participation in the rains.

The descent of the celestial energies, their sojourn on earth (or in the underworld), and their subsequent return to the heavens, form a cycle, a permanent round of descent-and-ascent (the nocturnal and the diurnal). The deities constitute the energies of this constant course traversed between heaven and earth (and underworld), and each of them repeats this falling-rising opposition within itself-as do all things-as they perpetually dance, sing, paint, or weave the whole cosmos, of which they are the protagonists. In tandem, all of this is simultaneously reproduced within man, where the hierarchies or scaled planes are duplicated, extending from the most diaphanous plane of the ninth heaven, that is, from the eternal impassivity of the beginning, to the last subterranean world, the dark, boiling activity of the earth and its infernal deities.

Let us be clear that the highest gods of heaven communicate with earth through the mediation of the deities of the intermediate plane, that is, through the planets and stars-especially the Sun, the Moon, Venus, and the Pleiades-in close relationship with the harmonious measure of time, the atmospheric phenomena and the numina of thunder, thunderbolt (and lightning), the wind, and the rain, deities that are creative in their capacity as fecundating or regenerative.5 In general terms, we may say that the Mesoamericans conceived the cosmos as a gigantic being whose eyes were the sun and the moon or the stars, its breath (its breath of life) the wind, its voice thunder, its weapon (glance=arrow) thunderbolt, and its weeping the rain. What we have here is the idea of a divine thought that is expressed by the god's word as signified by his attributes, or-to put it in a different way-as signified by the planetary or atmospheric numina (hierarchized in levels or heavens), those children of the One God and of his Primordial Duality. These numina, in their dialectical struggle, succeed in producing the necessary (fertilizing and regenerative) reaction on the part of the deities of earth. These latter, through their cooperation, are able to complete the ordained cycle, which gives rise to universal life, and thus establish the equilibrium of the cosmos through the possibility of their re-ascent to their origin. They execute this final movement in the cycle as a sacrificial offering to the ultimate deity, whose sustenance is, symbolically, life, burgeoning vegetation, maize, and animals, as well as man. Logically enough, the most popular gods are those of the earth and the atmosphere, since their very condition makes them more accessible to the majority of people, while the astral or celestial deities, being more exalted and abstract, are, precisely in virtue of their intangible nature, more remote. This same hierarchization exists within each individual awareness with respect to the process of Knowledge. In the schema of the Aztec civilization, the most abstract corresponds to the highest heaven and to the priestly caste. The material corresponds to the lowest, and to the caste of the macehualli. The central point is occupied by the sun-the warrior caste-as child and grandchild of the divine Father and Grandfather, and by the moon as his consort. It is to the sun, however, that the attributes of the highest gods are transferred, and this coincides with the passage from the priestly caste to the warrior caste (from Quetzalcoatl to Huitzilopochtli), and to the estrangement of the highest deity in virtue of these cyclical laws that constitute the universe. A familiar instance of the inversion of the falling-and-rising pattern is the case of fire. As a heavenly principle, it is a descending one. The Aztecs saw it in three stars (mamalhuaztli), in whose image was produced, by friction between two of them, physical fire. But as a terrestrial realization, obviously, it is an ascending one. Nevertheless these two fires are analogous-representations of a single, polarized principle. They are conjoined in man, who is able to understand this primordial inversion, and to utilize this earthly fire as an image derived from a common origin, which, from this perspective, then presents itself as rising, that is, as a return to the identity of its essence.6 We have the paradox of falling deities being the highest, and rising deities the lowest. This comes clear in relation to the double path to be traversed, and the inversion-and analogy-obtaining from either viewpoint, which in man is translated as a contradiction between his two natures, and the perspective adopted with respect to these. Let us observe as well that Ometecutli-the dual lord-sent his warmth and his emanations to those with child, to those who were to generate, those who were to give life on the earth. Let us recall, besides, that those who had died in childbirth were regarded as warriors, and as such, as accompanying the sun in part of its triumphal course. On the other hand, the deities of the rain are also particularly magical, seeing that it is their constant activity that produces the fructification of the earth, that produces life, and their perpetual going forth and returning is considered sacred: their descent as water, and their return to the skies-upon contact with earth, where they are transformed into mist and cloud-thence to descend anew, wounded by thunderbolt, once more to fertilize the world. There is no people who have not known this process, however little they may explain it in scientific or philosophical terms. Let us likewise note that the blood of the sacrificed, that sacred liquor, was denominated "precious water" (chalchihuatl). Like pulque, this liquid combined within itself the symbolical contradiction of water and fire, and harmoniously combined, in the body of the sacred, without any prejudice, "evil" and "good," its vice and its virtue.7 There are dozens of Precolumbian examples of what we are asserting, and they may perhaps be noted with greater facility in the divinities of the Indians of North and South America, the Caribbean, and the Mayan region, than in the more complex, many-faceted pantheon of the Aztecs-seething as the latter is with numina locked in constant dynamic combat, and possessing interchangeable attributes. Furthermore, we now know that listing the gods is not the same as speaking of the deity or of the concept of the sacred. Nevertheless, the divine attributes-that is, the identification of the deities and their functions-has its importance for a reading of the Mesoamerican codices, where these deities appear in combination with numbers, months, days, and other numina and expressions of the sacred, in a dance of swirling colors, in a kaleidoscope of meanings.8 Other themes that invariably appear-for example, that of duality (couples, twins), that of the hierarchy between the worlds or heavens (father, sons, gods, intermediaries, and so forth), that of maternal virginity, the deluge (with regard to the great eras), creation by word, and that of the return of the deity at the close of the cycle-are the themes that relate to the course of the sun, the moon, and Venus. These bodies are the heavenly voyagers par excellence, and their unvarying career marks the guidelines of the model of the cosmos. They all sail through the sky-each on its own course-across the starry ocean, from the line of the eastern horizon to their setting in the west, where they disappear, to die in the underworld-that country of the deceased, of dissolution, of night, of larval forms-which they traverse, to triumph over death and to be born anew, and grow, and execute the cycle once more. The sun descends by one gate (the western hoop in the game of ball) and ascends by the other (the eastern hoop), after having endured exile, imprisonment, and death in the underground world, to resurrect as a heavenly body that puts further away the darkness and evil that oppose it. For the Egyptians, this trajectory was effected within the body of the goddess Nut, who doubled up-forming four columns with her arms and legs-and gave birth to her child the sun, who was reabsorbed by her at the close of day. The symbol of the serpent with two heads, one at each end of its body, is found across the length and breadth of ancient America. Indeed it is practically universal (as in the Greek and Roman amphisbaena). In Mesoamerican symbology, this strange animal is customarily assimilated to heaven-and-why not?-to the earth, inverted counterpart of heaven, as if both were the two halves of a sphere or a square in the form of a losange, that is, the symbolical figure of a double pyramid (or cone) joined at its base. The serpent devours the sun, which emerges once more from its gullet at the other end. Some authors point out its iconographic resemblance to the Far Eastern dragon. In all traditions, these two doors (or symbols of passage) have been set in relationship with the year and its two solstices and two equinoxes (or with the dry and rainy seasons), those functions of the everlastingly repeated cosmic cycle. This circumstance renders these "voyagers" genuine intermediaries and lords: through their behavior, they reveal the cosmic plan, and accordingly, the thought of their creator, which transforms them into hierophants or psychopompoi-that is, into divine messengers, initiators into the mysteries and the sacredness of life. We find the equivalent in the Precolumbian man, who, through the rites of initiation, reiterates the creative deed, assisting at the generation of a luminous, ordered world, ever new and intact within himself, and bestowing validity and reason upon his existence. After all, being the child of mother earth (like maize), which has been fecundated by heaven, man arises as an intermediary that assembles both principles, and this bestows upon him the capacity to ascend, to return once more to heaven, thence to descend once more, if necessary, executing the fulfillment of the cyclical law.9 This may be the basic characteristic of the Archetypal, Original Oneness of the various traditions. In any case it is found in one form or another throughout all societies and their symbols, whether or not these cultures have produced high civilizations. |